After 50 years of progress, how prepared are

women for retirement?

Trends and Issues

June 2022

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 prohibits sex

discrimination (including pregnancy, sexual orientation, and gender

identity) in any education program or activity receiving federal nancial

assistance.

In the 50 years since the enactment of Title IX, women have made

enormous strides in terms of educational attainment, work, and

earnings. Although a wage gap by gender persists, women’s progress

in the workforce has clearly enhanced their economic status as

individuals. On the other hand, women have chosen to spend less

of their adult life married, and the decision to eschew the potential

support of a spouse could have put them more at risk economically.

This study uses the Health and Retirement Study to document the

economic gains and the changing demographic proles of women and

then assesses the extent to which they are prepared for retirement.

Since the trends in both economic gains and marriage have differed for

Black and White women, the results are reported by race as well as for

all women.

Alicia H. Munnell

Center for Retirement

Research, Boston College

TIAA Institute Fellow

Siyan Liu

Center for Retirement

Research, Boston College

Laura D. Quinby

Center for Retirement

Research, Boston College

Any opinions expressed herein are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of TIAA, the TIAA Institute or any other organization with which the authors

are afliated.

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 2

This review shows that women have gained in educational

attainment, work force activity, and earnings, and this

progress has translated into wealth. Moreover, women

do not appear to have undone their economic gains since

Title IX’s passage by opting to spend more time on their

own—those who spend the majority of their adult life

single are as well prepared for retirement as married

couples.

Overview

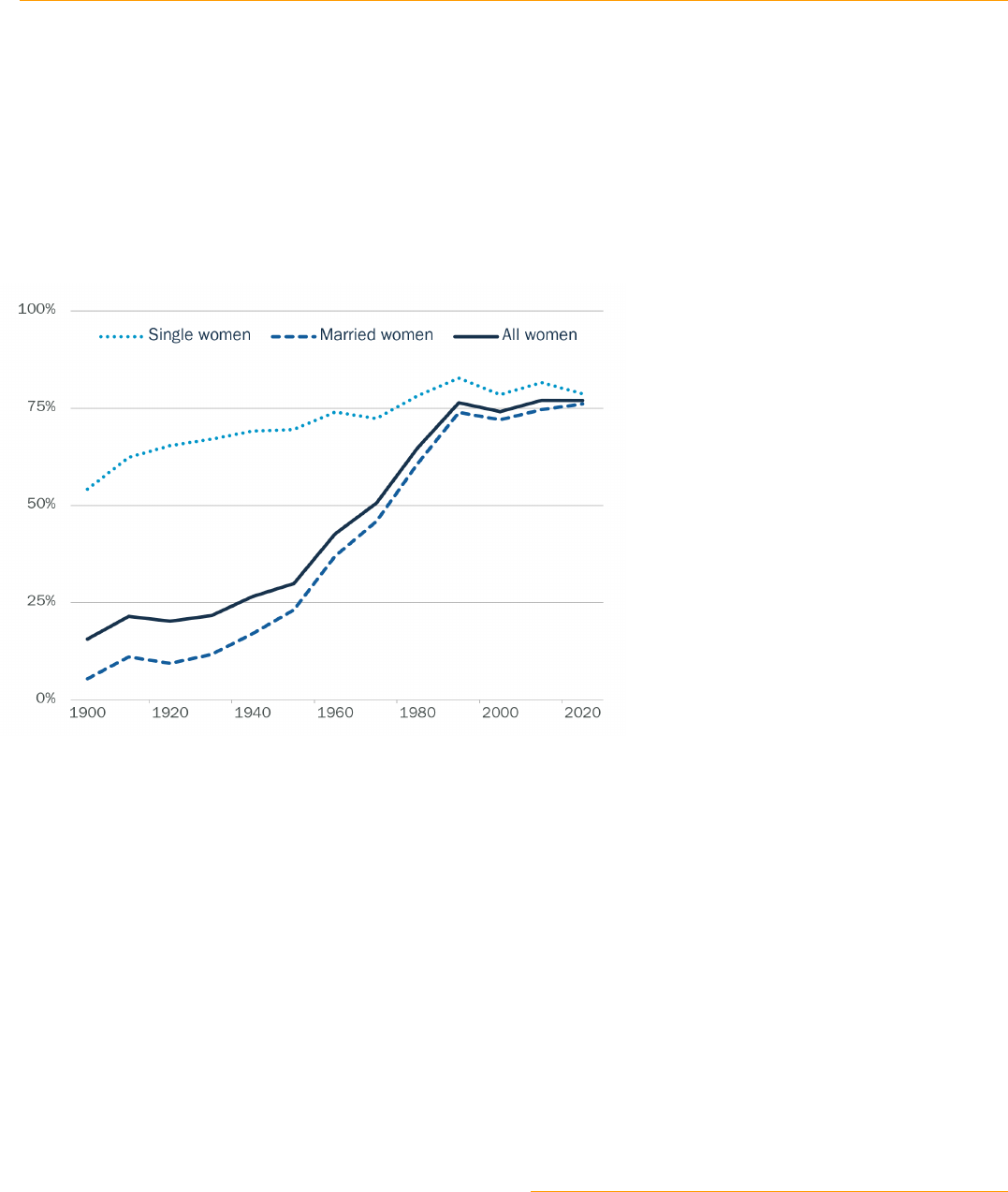

The short story is that single women have always

worked, but married women have not (see Figure 1). As

time passed, some married women started to work and

some did not, and this variability made the labor supply

of married women the subject of an enormous body of

research.

Figure 1. Labor force participation of single, married, and all women, ages 35–44, 1900-2020

Although this study focuses on changes in the half

century since Title IX, it is helpful to take a step back

and start the discussion with a look at the work habits

of married women over a longer period. Claudia Goldin

divides the history of women and their labor force activity

into four periods.

1

Late 19

th

Century to the 1920s. Some young and

non-married women worked as piece workers in

manufacturing or as maids. However, virtually no married

women were in the labor force. Because work was

generally very unpleasant, a huge stigma was attached

to wives working outside the home. Only the poor needed

their wives to work at physically demanding jobs that

involved long hours. Economists have estimated income

and substitution effects associated with women’s

labor force activity over time. That is, how responsive

is the wife’s labor supply to the household’s income,

typically the husband’s earnings, and to the wage she

can earn in the labor market. During this period, as the

husband’s income increased above fairly modest levels,

the likelihood that a married woman would work declined

substantially. At the same time, an increase in the wage

was unlikely to coax additional work activity on the part of

women.

1930s to 1950. During these two decades, the labor

force activity of prime-age married women rose from

10 percent to 25 percent. One reason is that jobs got

less physically demanding and more appealing—ofce

jobs rather than manufacturing jobs. New technologies,

such as in-home appliances also made housework less

1 Goldin (2006).

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (1900-2020).

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 3

time-consuming. And the possibility of working part-

time arose in the 1940s and became widespread in the

1950s, which was attractive to women who were primarily

responsible for home and children.

1950s to 1970s. In this period, the labor force

participation of prime-age married women rose from

25 percent to almost 50 percent. The demand for

women’s labor was strong. Many entered the labor force

as secretaries, teachers, and nurses. While they came

fully trained to these positions, many did not expect

advancement, and treated their work as a job not as an

element of their identity. Yet they ended up spending a

substantial portion of their life employed.

2

1970s to the Present. Young women growing up in the

1960s could see that it was feasible to spend most

of their lives employed. One way they responded was

to invest in their education. They went to college in

increasing numbers, majored in career-oriented subjects,

and were more likely to continue their education in

professional and graduate schools. The advent of the

contraceptive pill allowed many to postpone marriage

and establish themselves professionally. As many placed

their career on equal footing with their marriage, the labor

supply of married women became even less responsive

than before to their husband’s earnings.

Progress from the 1970s to the present

Since this study focuses on the 50th anniversary of

Title IX, the analysis looks at the achievements of

women in terms of education, work, and earnings since

the enactment of that legislation. The data come from

the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a longitudinal

nationally representative survey that has interviewed

people over age 50 every two years since 1992 (most

recently 2020). The survey contains information on ve

cohorts of respondents. The original HRS cohort (born

1931-41) and the War Babies (1942-47), who reached

age 20 in the 1950s and the 1960s, can serve as a

base of comparison. The Early Boomers (1948-53), Mid

Boomers (1954-59), and Late Boomers (1960-1965),

who reached age 20 in the 1970s and 1980s, show the

economic gains since the passage of Title IX.

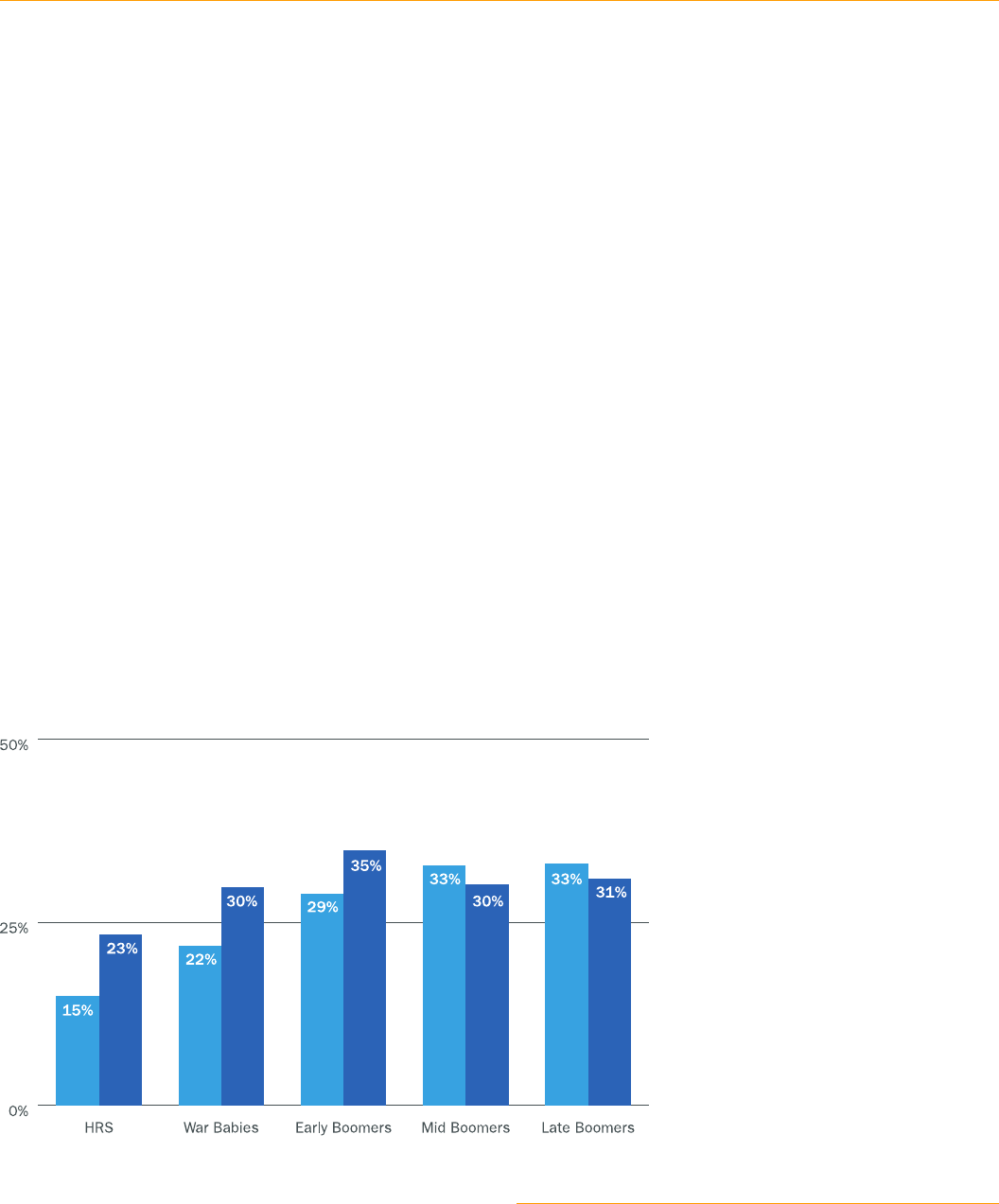

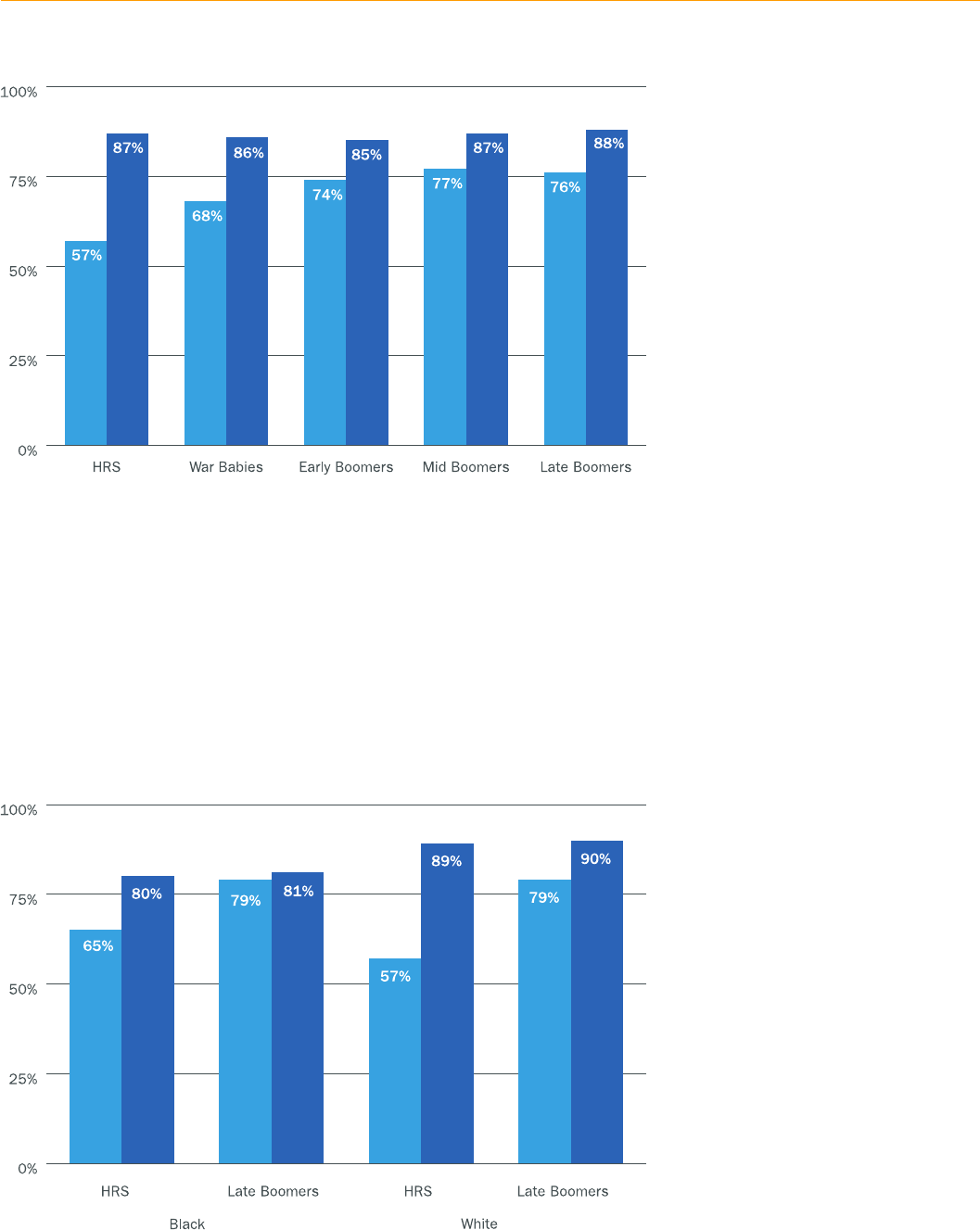

To provide a sense of progress on the educational front,

Figure 2 shows the percentage of women and men who

ended up with a college degree. Two facts stand out.

First, the share of women with a degree has increased

enormously, from 15 percent for those born in the 1930s

to one third for Late Boomers, born in the early 1960s.

Second, for recent cohorts, a greater percentage of

women than men ended up with a college degree.

Figure 2. Percentage of women and men with a college degree, by cohort

Source: Authors’ calculations from the University of Michigan, Health and Retirement Study (HRS) (1992-2020).

2 Goldin (2006).

● Women

● Men

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 4

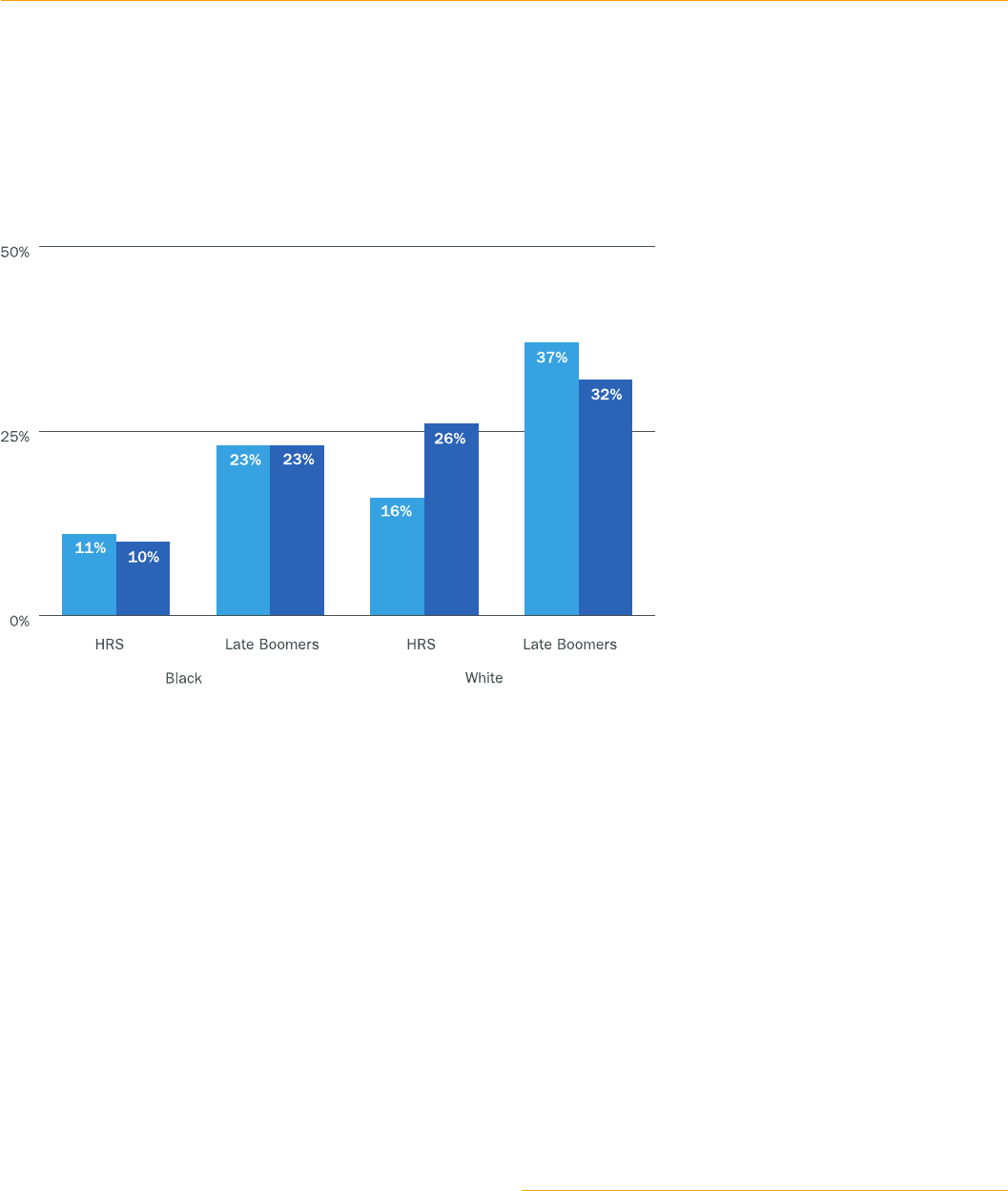

That pattern by gender reects the outcome for Whites,

where the percentage with a college degree is ve

percentage points higher for women than for men

(see Figure 3). For Blacks, the percentages for the two

genders are equal. Figure 3 also shows that, while the

outcomes for both Black and White women have improved

markedly, educational progress for Black women has

lagged behind that of their White counterparts.

3 Around 60 percent of HRS respondents agree to link their survey data with

administrative earnings records from the Social Security Administration.

Figure 3. Percentage of women and men with a college degree for HRS and Late Boomer cohorts, by race

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

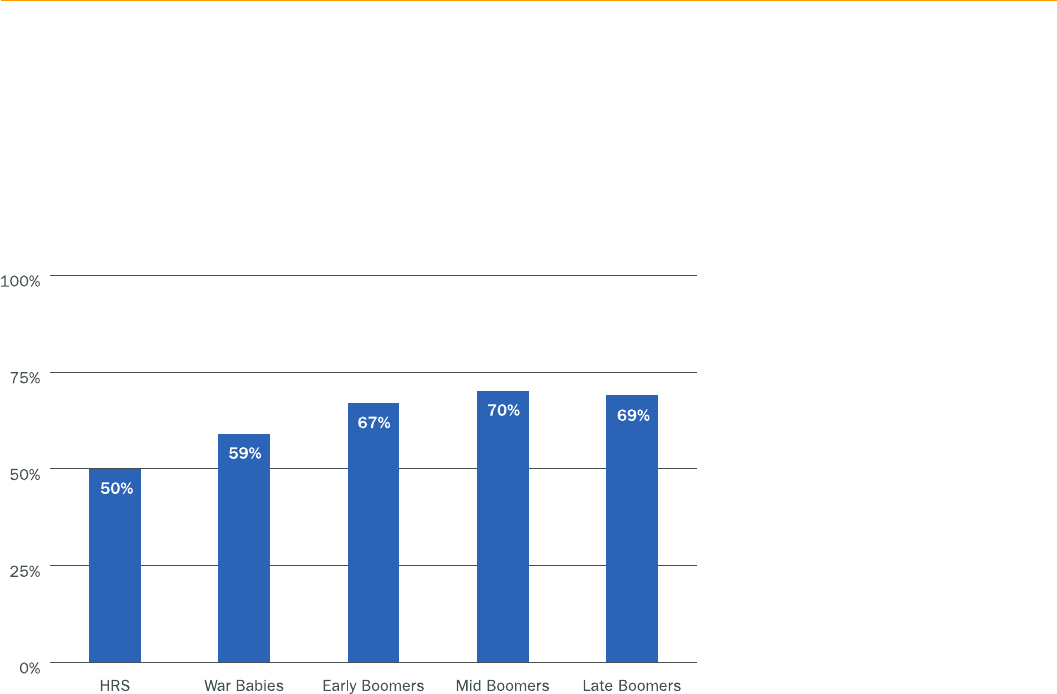

The next two gures repeat the same exercise for labor

force activity. Although the HRS does not interview people

until age 50, administrative data on lifetime earnings

is available for a large subsample.

3

Figure 4 shows

the labor force participation rate for women and men

between ages 35-44 for the ve cohorts. The percentage

of prime-age women in the labor force increased from

57 percent for the earliest cohort to 76 percent for the

Late Boomers. The increase has markedly reduced the

differential between women and their male counterparts

for whom labor force participation rates have remained

relatively constant between 85 percent and 88 percent.

● Women

● Men

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 5

The pattern by race is interesting. As expected, in both

cases, women’s increased participation has narrowed

the gender gap. But because historically more Black than

White women worked—perhaps out of necessity—the

increase in participation for White women has exceeded

those for their Black counterparts (see Figure 5). This

more rapid increase for White women, combined with a

lower starting point, has produced an equal labor force

participation rate for prime-age Black and White women.

Finally, because the participation rate for Black men is

about 10 percentage points lower than for White men,

the gender gap has virtually disappeared for Blacks but

remains for Whites.

Figure 4. Labor force participation rate of individuals ages 35–44 by cohort

Figure 5. Labor force participation rate of individuals ages 35–44 for HRS and Late Boomer cohorts, by race

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

● Women

● Men

● Women

● Men

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 6

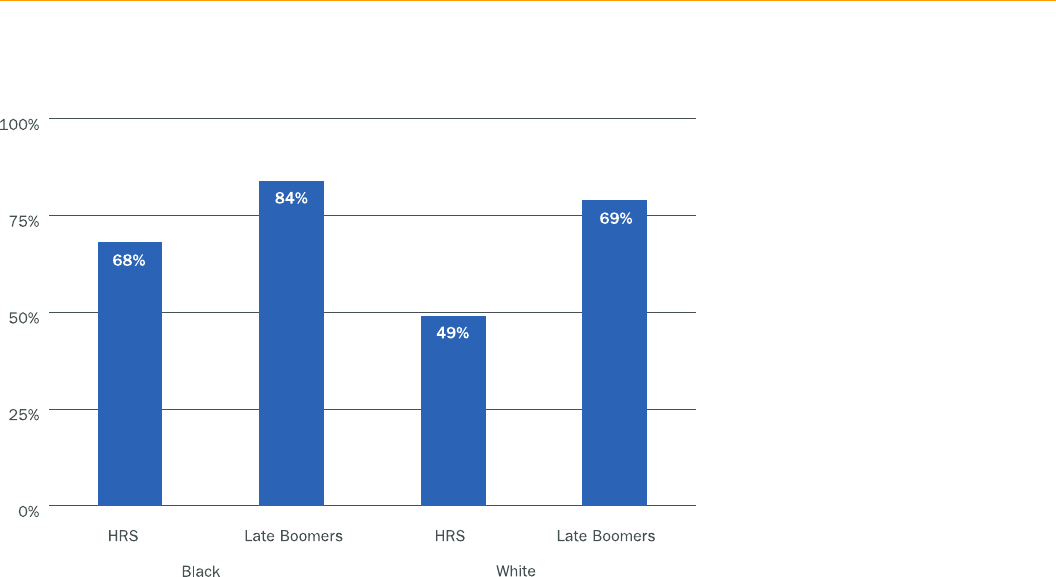

Not surprisingly, the increased educational attainment

and greater labor force activity of women have led to

higher earnings. Unfortunately, the HRS administrative

earnings data do not have information on hours worked,

so in order to identify full-time workers it is necessary to

turn to the Current Population Survey. For this exercise,

we assigned workers to cohorts based on their year of

birth and then observed them at ages 35-44. The results,

reported in Figure 6, show that women’s earnings have

increased from 50 percent of men’s to about 70 percent

for the Boomers.

Figure 6. Women’s earnings as a percentage of men’s, full-time individuals ages 35–44

Source: Authors’ calculations from the U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey (CPS) (1967-2009).

Repeating the exercise by race shows that Black

women, too, have gained relative to men (see Figure 7).

Interestingly, both historic and current ratios are higher

for Black than for White women. This pattern, however,

says more about the low earnings of Black men, as the

earnings of full-time Black women are quite similar to

those for their White counterparts.

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 7

In summary, the economic life of women has changed

dramatically. More have graduated from college, more

participate in the labor force, and they earn more relative

to men. Women’s progress in the workforce has clearly

enhanced their economic status as individuals. The

question for this report, however, is the extent to which

women are prepared for retirement. That answer depends

not only on the economics of women as individuals,

but also their living arrangements. To the extent that

women have moved away from marriage and eschewed

the potential support of a spouse—who is more likely

to have a better job and higher earnings—both during

their working life and in retirement, they could have put

themselves more at risk economically.

The decline of marriage

To quantify the extent to which marriage patterns have

changed, we once again turn to the HRS to calculate

the percentage of each woman’s adult life (ages 20 +)

spent in marriage. For comparisons across cohorts, one

would like to include in the calculation all years between

age 20 and the death of the respondent. Such a broad

span is not possible, however, because women added

to the sample in recent years are still quite young. For

example, the Late Boomers were added in 2016, so as

of 2020 this group includes women who were only in

their mid-to-late 50s. As a result, estimates need to be

made for these later cohorts. Three sets of calculations

are presented to illustrate that the assessment is not

particularly sensitive to the approach taken.

To establish a baseline requiring no estimates, the

starting point is marriage patterns between age 20 and

the most recent interview. The number of years over this

span is totaled for each woman and then added across

all women to get “total women years.” The number of

years married during this span is then totaled for each

woman and added over all women to get “years married.”

Dividing “total years married” by “total woman years”

yields the percentage of years married for each cohort.

One concern with using age 20 to the last interview is

that the Late Boomers in 2020 were 54-60, while the

original HRS cohort in 2020 were 79-89. Therefore, the

“last-interview” results could understate the decline

because the most recent cohorts have spent virtually

no years as widows. To address this concern, a second

approach uses a standard age for each cohort. Of

course, excluding information at older ages when women

are more likely to be widowed increases the percentage

of years married throughout, but most likely provides a

better picture of decline over time.

Figure 7. Women’s earnings as a percentage of men’s, full-time individuals ages 35–44, by race for HRS

and Late Boomer cohorts

Source: Authors’ calculations from the CPS (1967-2009).

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 8

The nal approach takes advantage of all the available

data and makes an estimate for potential widowhood for

younger women. This estimate starts with the ratio of the

percentage of years spent married for the HRS cohort as

of last interview (79-89) to the percentage for this same

cohort at ages 54-60 (71/77 = .92). This ratio, which

shows how the percentage of years married is reduced

when more years are included, is applied to the reported

percentages at ages 54-60 for the younger cohorts.

The results for all three calculations are shown in Table

1. Regardless of the approach taken, the percentage of

women’s adult years spent married has declined sharply

from over 70 percent for the HRS cohort to an estimated

44 percent for the Late Boomers.

How did this dramatic change come about? First, the

average age of rst marriage rose by about 4 years

between the HRS cohort and the Late Boomers (see

Table 2).

4

Second, a greater proportion of women never

4 Haines (1996) documents an increase in the age at rst marriage for women that

began in 1950 and continued through 1990. Loughran (2002) attributes some of

this increase to rising male wage inequality over the same time period. Goldin and

Katz (2002) attribute some of the increase to the introduction of the birth control

pill in the 1960s.

5 As Stevenson and Wolfers (2007) note, divorce rates actually peaked in the early

1980s and have fallen slightly since. In this context, the sharp increase in the

share of women divorced between the HRS cohort and Early Boomers (who would

have been in their 30s around the time of the peak) makes sense, followed by the

slight decline seen for the Mid Boomers.

marry, rising from 4 percent in the HRS cohort to 15

percent for Late Boomers. And third, more women get

divorced.

5

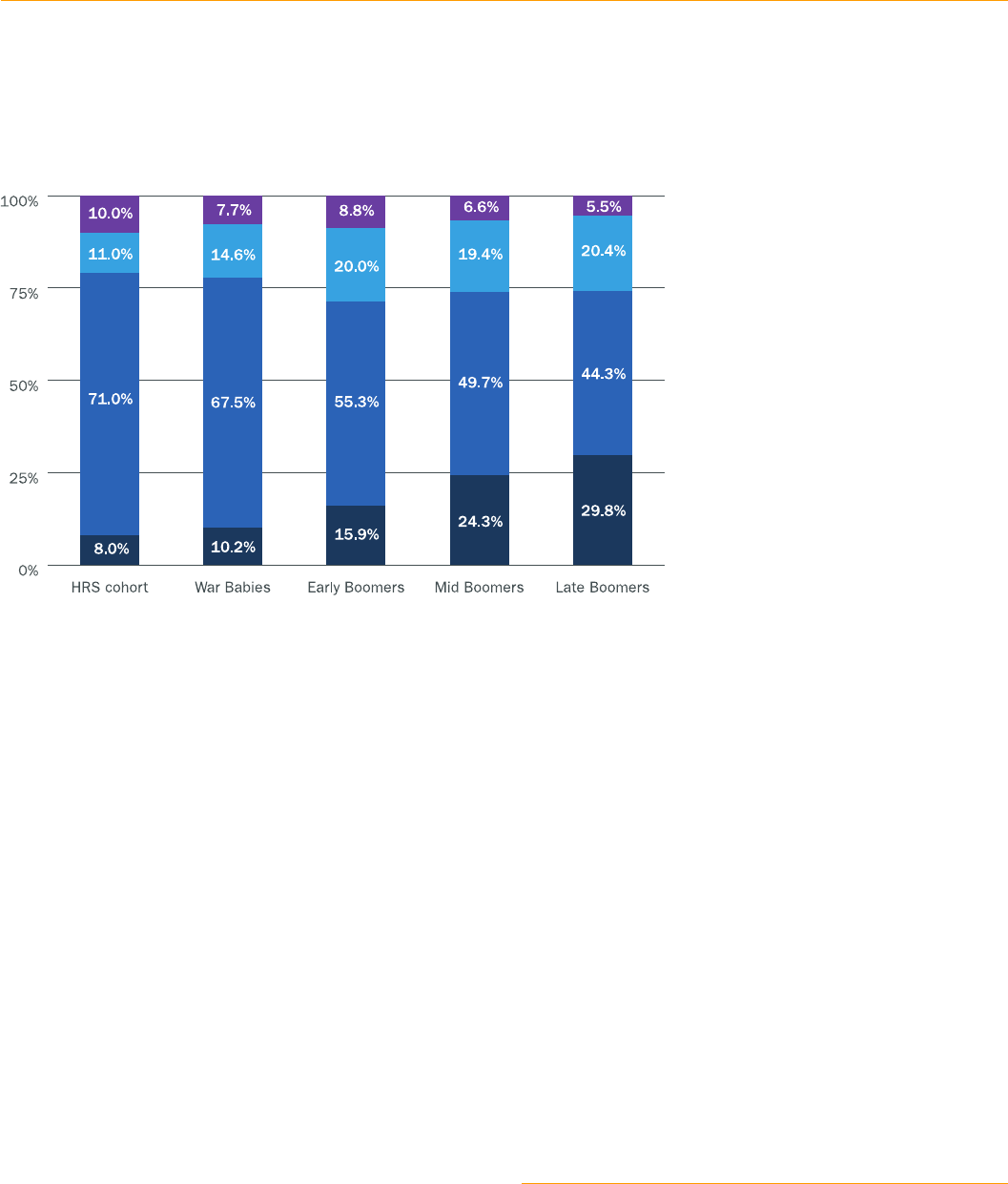

Table 1. Percentage of years that women spend married by cohort, 2020

Age span HRS Cohort War Babies Early Boomers Mid Boomers Late Boomers

Ages 20 to last interview 71.0% 71.2% 59.3% 54.5% 48.1%

Ages 20 to 54–60 77.1 73.2 60.0 54.0 48.1

Ages 20 to 79–89 (est.) 71.0 67.5 55.3 49.7 44.3

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

Table 2. Women’s marriage patterns by cohort, 2020

Marriage pattern HRS Cohort War Babies Early Boomers Mid Boomers Late Boomers

Avg. age of rst marriage 21.4 21.6 22.8 24.3 25.3

% never married 3.9% 4.2% 8.7% 11.9% 14.6%

% divorced

*

34.1 38.7 49.2 48.3 49.7

*Includes any woman who was ever divorced.

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2014).

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 9

The impact of these changing patterns on the percentage

of “woman years” married is shown in Figure 8. The

substantial increase in years spent either divorced or

“not married” (i.e., prior to a rst marriage or because the

individual never got married) has reduced the percentage

of years married.

Figure 8. Percentage of years widowed, divorced, married, and not married, by cohort

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

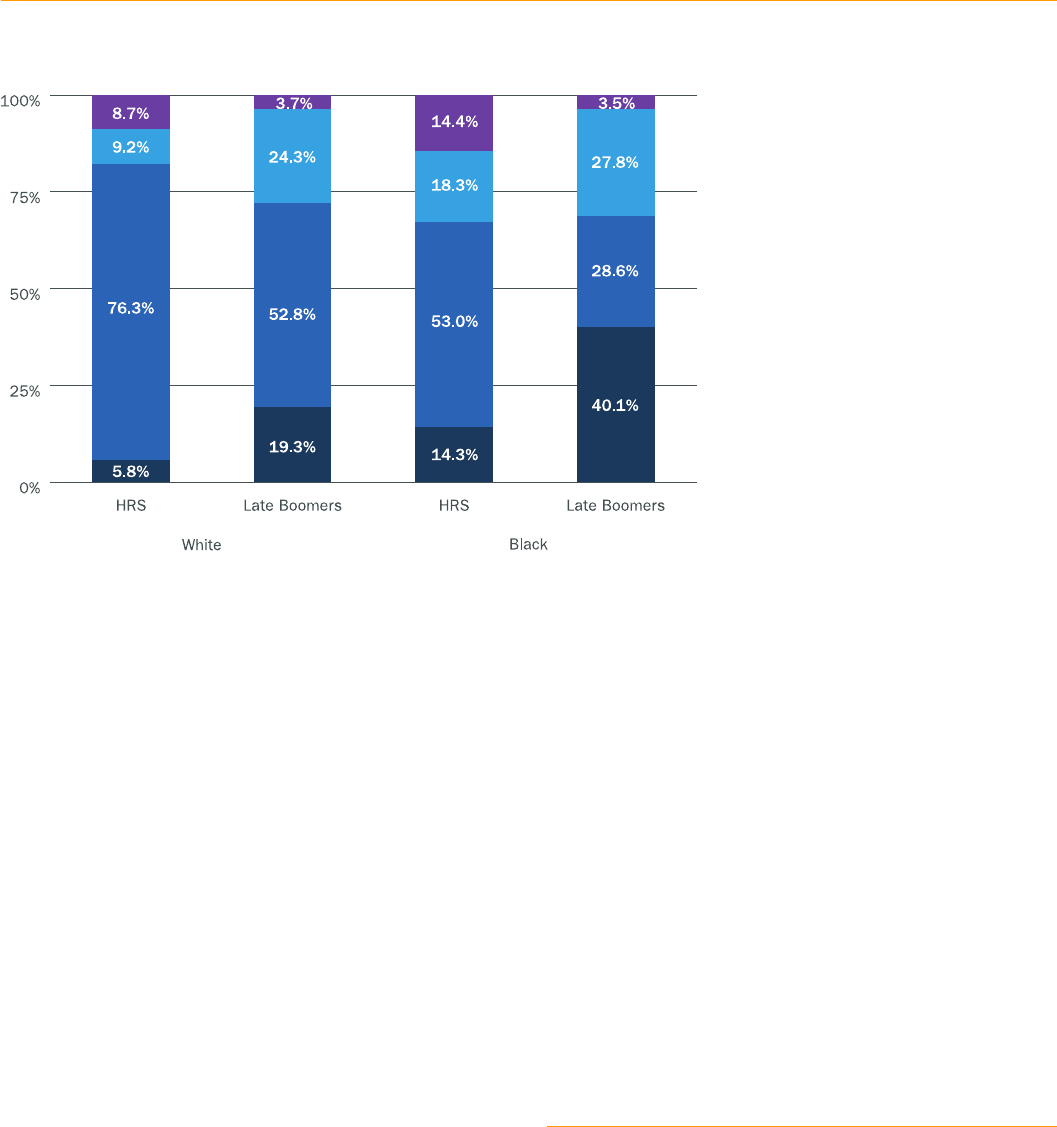

While women in the aggregate are spending less and less

time in marriage, the question is whether this decline is

similar across socioeconomic groups. To examine this

issue, we replicate the exercise for Whites versus Blacks

and for those with a college degree versus those with

less than college. For simplicity, we compare only the

HRS cohort with the Late Boomers.

While the percentage of years married declined

signicantly for both White and Black women, three

differences are worth noting (see Figure 9). First, Black

women have always spent a smaller percentage of years

married than White women have. Second, the decline

in the percentage of years married is greater for Black

women than White women.

6

Third, the reasons for the

decline are different. Whereas White women saw a more

than doubling of years spent divorced, Black women did

not. In contrast, Black women experienced a much larger

increase in the percentage of years not married, making

it the single largest category for them.

6 Both the lower level of marriage among Blacks and the widening marriage gap have

been documented elsewhere, for example in Raley, Sweeney, and Wondra (2015).

● Widowed

● Divorced

● Married

● Not married

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 10

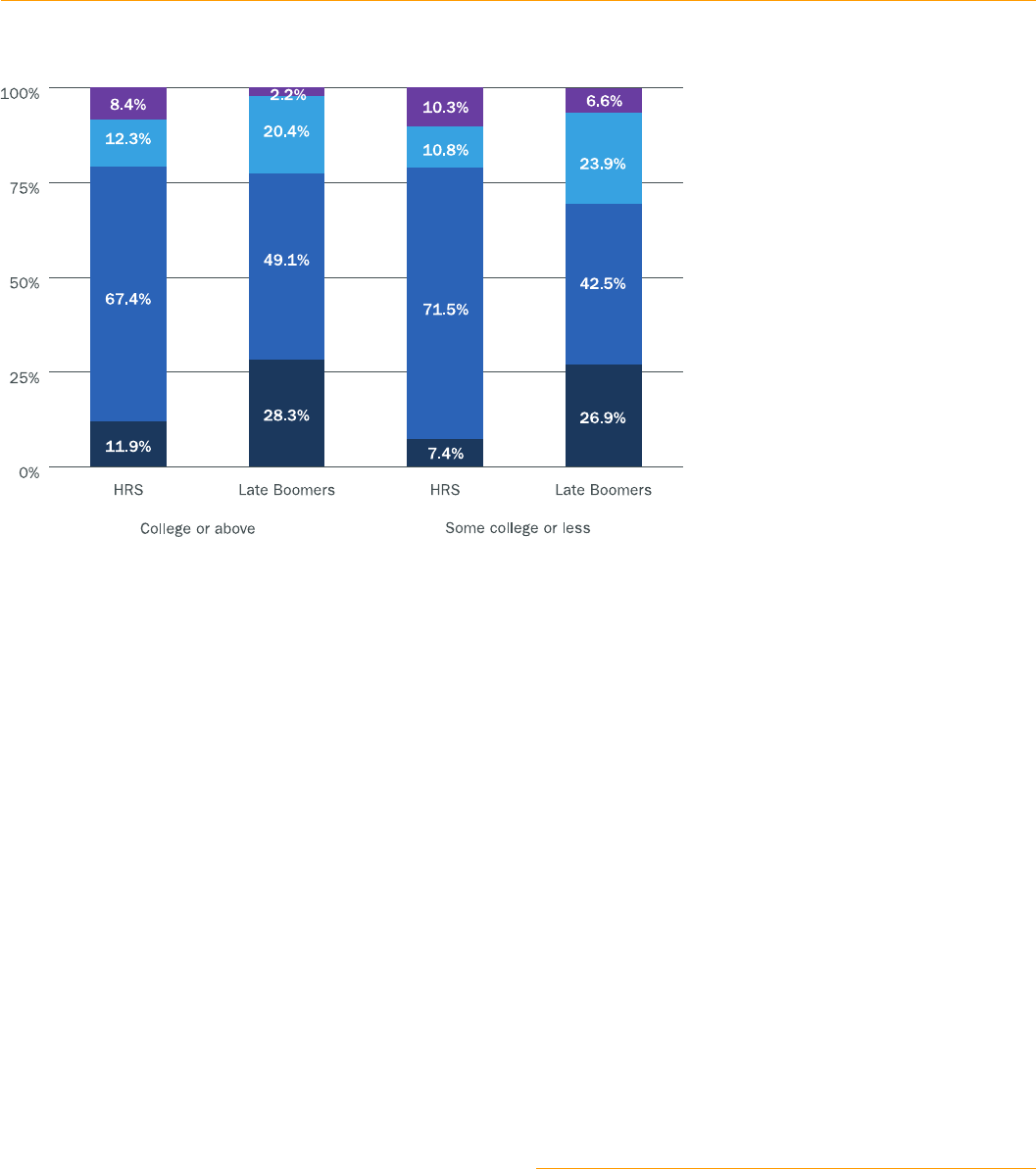

In contrast to the enormous difference in marital patterns

by race, the pattern by educational attainment looks

very similar (see Figure 10).

7

For both those with a

college education and those with less than college, the

percentage of years spent married declined from about

Figure 9. Percentage of years widowed, divorced, married, and not married, by cohort and race

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

7 Statistics are restricted to females who enter the HRS survey before age 60.

Observations are selected at the last wave in which the individual falls within ages

52-58, inclusive.

8 Although recent evidence has suggested that these numbers may diverge for

future birth cohorts of women, at least through the Mid Boomer cohort, the trends

look similar. For example, Lundberg, Pollak, and Stearns (2016) nd that the

marriage rates of 30- to 44-year-olds between those with and without a college

education were very similar through the mid-1980s (when the Mid Boomers would

have been in their 30s) and have been diverging ever since.

70 percent to about 45 percent between the HRS and

Late Boomer cohorts. The increase in the percentage of

years not married or divorced was also consistent across

educational groups.

8

● Widowed

● Divorced

● Married

● Not married

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 11

Figure 10. Percentage of years widowed, divorced, married, and not married, by cohort and education

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

The bottom line is that women as a group have moved

from a situation where they spend most of their adult life

married to one where they spend less than half of their

adult life as part of a couple. Thus, to assess retirement

preparedness of women, it is necessary to consider both

changes in family structure as well as patterns of wealth

accumulation by cohort.

Changes in wealth accumulation and

retirement preparedness of women

The ultimate goal of the analysis is to determine the

extent to which women are prepared for retirement

and how their situation may have changed over time.

9

Preparation for retirement is measured in two ways.

(Details of both calculations are presented in the

Appendix.)

The rst is household wealth, which includes: 1) Social

Security wealth as measured by the expected discounted

value of future benets; 2) wealth in employer-sponsored

retirement plans, including both 401(k)-type and IRA

balances and the present discounted value of expected

benets from a dened benet plan; 3) nancial assets

less any outstanding debt; and 4) the value of the

primary residence less any outstanding mortgage debt.

While wealth measures provide useful insights into trends

across cohorts, the ultimate purpose of that wealth is

to allow households to maintain their standard of living

in retirement. Therefore, preparation for retirement is

also measured in terms of replacement rates—the ratio

of the retirement income that could be generated by

a household’s retirement resources divided by its pre-

retirement income.

Table 3 shows how wealth has changed across cohorts

for women and men. One decision is how to characterize

the wealth of one member of a married household. This

analysis assigns the couple’s full value to the woman and

to the man. Although this approach clearly overstates the

holdings of married people, it provides a clear benchmark

against which to compare trends over time. The numbers

are presented in 2020 dollars and represent the average

for the middle quintile of the wealth distribution.

9 This stage of the analysis will expand on Hou and Sanzenbacher (2021), who

assess retirement preparedness for households in the HRS by race and ethnicity.

The analysis will compare retirement readiness when the head of household is

ages 58-61 (age will vary depending on birth cohort and the timing of HRS survey

interviews).

● Widowed

● Divorced

● Married

● Not married

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 12

Two patterns are evident in Table 3. First, wealth has

been declining across cohorts for both men and women.

This decline is largely due to two factors: 1)lower Social

Security wealth asthe increase in the Full Retirement Age

reduced benets for all; and 2) fewer assets in retirement

plans because of adverselabor market experiences

during the Great Recession. The second, and for the

purpose of this study, more interesting result is the

ratio of women’s wealth to men’s wealth. For the earlier

cohorts, the women’s wealth equaled 82-85 percent of

men’s; for the later cohorts, the comparable gures were

90-93 percent. Boomer men, who did not enjoy gains in

education or earnings over time, appear to have been hit

much harder than their female counterparts by the Great

Recession.

The question is the extent to which the overall

improvement in women’s wealth relates to their marital

status. Table 4 presents the wealth holdings for three

groups of women: 1) never married; 2) mostly single (less

than 50 percent of adult years married); and 3) mostly

married (more than 50 percent of adult years married).

The large decline in median wealth for women who

spend their lives mostly married largely reects declining

fortunes for their husbands, who felt the full impact of

reduced Social Security wealth and the Great Recession

without a countervailing increase in earnings. Since the

wealth of the mostly-single and never-married women has

remained relatively stable, their holdings have increased

sharply relative to the mostly married. For the Late

Boomer cohort, the relevant percentages are 65 percent

for the mostly-single and 48 percent for the never-married

women. Those percentages are high, given that, as noted

above, the mostly-married wealth belongs to two people.

Thus, in terms of wealth, women do not appear to have

undone their economic gains by changing their marriage

patterns.

Table 3. Median retirement wealth at ages 59–60 for households by gender and cohort, 2020 dollars

Table 4. Median wealth at ages 59–60 for women by lifetime marital status and cohort, 2020 dollars

Cohort

Gender HRS Cohort War Babies Early Boomers Mid Boomers Late Boomers

All women $480,600 $543,500 $445,000 $379,800 $335,400

All men 588,700 638,900 479,600 419,800 373,300

Women's wealth as a % of men's 82% 85% 93% 90% 90%

Cohort

Lifetime marital status HRS Cohort War Babies Early Boomers Mid Boomers Late Boomers

Mostly married $579,400 $731,400 $646,000 $530,700 $446,400

Mostly single 226,500 333,800 285,600 259,700 290,400

Never married 297,400 226,200 232,600 223,400 216,000

As a % of mostly married;

Mostly single 39% 46% 44% 49% 65%

Never married 51

*

31 36 42 48

Note: Median is measured as the average for the middle quintile of the wealth distribution.

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

* This number appears to reect noise from a small sample size rather than the earnings of never-married women.

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 13

Table 5 repeats the same calculations for Black women.

Because the sample sizes by cohort, race, and marital

status are relatively small, the calculations collapse the

pre-Title IX cohorts—the HRS and the War Babies—and

those who mainly entered their 20s after Title IX—

namely, the Early, Mid, and Late Boomers. Although the

wealth levels are lower for Black women than for women

in general, the pattern of mostly-single and never-married

women gaining on the mostly married is similar to that of

women generally.

Table 5. Median wealth at ages 59–60 for Black women by lifetime marital status and cohort, 2020 dollars

Cohort

Lifetime marital status

HRS/

War Babies

Early, Mid, and

Late Boomers

Mostly married $334,600 $343,400

Mostly single 180,600 199,900

Never married 101,800 152,500

As a % of mostly married;

Mostly single 54% 58%

Never married 30 44

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

The ultimate purpose of retirement wealth, however, is

to support people’s pre-retirement standard of living in

retirement. So, Tables 6 and 7 repeat the exercise for

replacement rates, projected retirement income as a

percentage of pre-retirement earnings. In this exercise,

retirement income is based on annuitizing non-housing

wealth at ages 59-60 and pre-retirement income is set

at the ve years of highest earnings before age 55.

10

Housing is excluded because, as much as experts urge

them to do so, homeowners rarely tap their equity to

support themselves in retirement. The level of reported

replacement rates is lower than they will be ultimately,

because these households are 59-60 and still have

several years more to work and save before they retire.

The pattern of replacement rates across cohorts mirrors

the pattern of wealth in that mostly-single and never-

married women have gained relative to the mostly

married. But the story is slightly more complicated.

Mostly-married women have seen a sharp decline in

replacement rates due to two factors. First, the increase

in Social Security’s Full Retirement Age reduced benets

for all. While women’s improved economic success

acted as a countervailing force, men had no offsetting

gains and, therefore, absorbed the full impact of the FRA

increase. Second, household replacement rates have

further declined as the increased labor force participation

of married women has led to a dramatic decline in

the prevalence of the 50-percent spousal benet. (At

the extreme, if both members of a couple have the

same earnings, they get no spousal benet and their

replacement rate is equal to the husband’s rate alone,

whereas a household getting a full spousal benet would

have a replacement rate that is 50 percent higher.)

11

At the same time, never-married Boomers have seen

higher replacement rates than the earlier cohorts, while

replacement rates for the mostly-single women have

declined only slightly. Again, the conclusion is that women

foregoing marriage for some or all of their life have not

sacriced economic security. Just as their wealth has

increased relative to their married counterparts, so too

have their replacement rates become more equal.

10 Non-housing wealth includes the discounted value of Social Security benets;

wealth in all employer-sponsored retirement plans and balances in IRAs; and

nancial assets less outstanding debt.

11 When most women did not work, the wife who claimed at age 65 was entitled

to a benet equal to 50 percent of that of her husband’s, so if the replacement

rate for the typical worker was 40 percent, the replacement rate for the couple

would be 60 percent. As women went to work, however, the calculation became

less obvious, since women were entitled to the larger of the spouse’s benet or

the benet they could earn on their own. When women’s earnings were modest,

their wages increased the couple’s pre-retirement income, but did not increase

the total amount the couple received from Social Security. As women’s wages

became equal to their husband’s, the replacement rate for the couple with two

typical workers would be 40 percent.

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 14

Finally, Table 7 reports replacement rates for Black

women—again comparing the HRS/War Babies and the

Boomers. Because of the progressive nature of Social

Security, despite having less wealth, Black women have

replacement rates roughly equal to those for women as

a group. And the pattern over time is similar. Women

who spend most of their life married have experienced

a decline in replacement rates, while the mostly single

and never married have seen increases. Like the story

for women as a group, the replacement rates for mostly-

single and never-married women have reached and now

even exceed those for women who spend their lives

mostly married.

Table 6. Median replacement rate at age 59–60 for women by lifetime marital status and cohort

Cohort

Lifetime marital status HRS Cohort War Babies Early Boomers Mid Boomers Late Boomers

Mostly married 44% 47% 44% 38% 35%

Mostly single 36 36 36 33 33

Never married 43

*

24 37 34 34

*This number appears to reect small sample size rather than the earnings of never-married women.

Note: Median is measured as the average for the middle quintile of the wealth distribution.

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

Table 7. Median replacement rate at age 59–60 for Black women by lifetime marital status and cohort

Cohort

Lifetime marital status

HRS/

War Babies

Early, Mid, and

Late Boomers

Mostly married 37% 33%

Mostly single 32 34

Never married 26 38

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992-2020).

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 15

Conclusion

In the half century since Title IX’s passage, women

have made substantial economic progress. The key

comparison in this study is between Baby Boomers, who

were reaching adulthood in the wake of Title IX, and prior

generations. Baby Boomer women are much more likely

to have college degrees and the Mid to Late Boomers

have even surpassed men on this metric. Women’s

labor force participation rates have also risen sharply,

particularly for married women. Not surprisingly, women

are earning more as well. The economic status of both

Black and White women has improved over this period,

though Whites have seen greater progress than their

Black counterparts.

While these economic advancements are encouraging,

the focus of this study is on the extent to which

women are prepared for retirement. One factor that

could potentially undermine women’s economic gains

during their working lives is a change in their living

arrangements. In recent decades, women are more likely

to live independently, with the Late Boomers spending

only 44 percent of their adult lives married compared to

over 70 percent for the oldest cohorts. Baby Boomers

are more likely to have married later, gotten divorced,

and never married at all. These overall trends have been

similar by race, but White women have seen a bigger

surge in divorces, while Black women have experienced

a larger increase in the never-married group. This

movement away from marriage, by reducing the potential

support of a spouse, could have put women more at risk

economically.

Strikingly, though, the results show that it is the women

who have spent most of their lives married who look

worse off in terms of retirement preparedness. Compared

to earlier cohorts, they have seen signicant drops in

their retirement wealth and in their replacement rates.

The reason is, in large part, the declining economic

fortunes of their husbands, who experienced the full

impact of the rise in Social Security’s Full Retirement Age

and labor market setbacks during the Great Recession

without countervailing improvements in education and

earnings. Additionally, mostly-married couples have

seen a drop in replacement rates due to their declining

eligibility for Social Security’s spousal benet. In

contrast, mostly-single and never-married women have

gained ground on those who are mostly-married. These

overall patterns are similar for both White and Black

women. The conclusion, then, is that women do not

appear to have undone their economic gains since Title

IX’s passage by opting to spend more time on their own.

They have gained both income and wealth, and are as

well prepared for retirement as married couples.

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 16

References

Butrica, Barbara A. and Karen E. Smith. 2012a. “The Impact of Changes in Couples’ Earnings on Married Women’s

Social Security Benets.” Social Security Bulletin 72(1): 1-10.

Butrica, Barbara A. and Karen E. Smith. 2012b. “The Retirement Prospects of Divorced Women.” Social Security

Bulletin 72(1): 11-22.

Butrica, Barbara A., Karen E. Smith, and Howard M. Jams. 2012. “This Is Not Your Parents’ Retirement: Comparing

Retirement Income Across Generations.” Social Security Bulletin 72(1): 37-58.

Fang, Chichun, Charles Brown, and David Weir. 2016. “Cohort Changes in Social Security Benets and Pension

Wealth.” Working Paper 2016-350. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Retirement Research Center.

Fang, Chichun and Kandice Kapinos. 2016. “Health and Retirement Study Prospective Social Security Wealth Measures

of Pre-Retirees.” Version 1.0. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research.

Goldin, Claudia. 2006. “The Quiet Revolution that Transformed Women’s Employment,Education, and Family.”

American Economic Review 96(2): 1-21.

Goldin, Claudia and Lawrence F. Katz. 2002. “The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women’s Career and

Marriage Decisions.” Journal of Political Economy 110(4): 730-770.

Gustman, Alan L., Thomas L. Steinmeier, and Nahid Tabatabai. 2010. Pensions in the Health and Retirement Study.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gustman, Alan L., Thomas L. Steinmeier, and Nahid Tabatabai. 2014. “The Great Recession, Decline and Rebound in

Household Wealth for the Near Retirement Population.” Working Paper 20584. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of

Economic Research.

Iams, Howard M., John W. R. Phillips, Kristen Robinson, Lionel P. Deang, and Irena Dushi. 2009. “Cohort Changes in

the Retirement Resources of Older Women.” Social Security Bulletin 68(4): 1-13.

Haines, Michael R. 1996. “Long-Term Marriage Patterns in the United States from Colonial Times to the Present.”

The History of the Family 1(1): 15-39

Hou, Wenliang and Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher. 2021. “Measuring Racial/Ethnic Retirement Wealth Inequality.”

Journal of Retirement 8(3): 12-28.

Loughran, David S. 2002. “The Effect of Male Wage Inequality on Female Age at First Marriage.” The Review of

Economics and Statistics 84(2): 237-350.

Lundberg, Shelly, Robert A. Pollak, and Jenna Stearns. 2016. “Family Inequality: Diverging Patterns in Marriage,

Cohabitation, and Childbearing.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30(2): 79-102.

Mitchell, Olivia S. and James F. Moore. 1997. “Retirement Wealth Accumulation and Decumulation: New Developments

and Outstanding Opportunities.” Working Paper 6178. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Mitchell, Olivia S., Jan Olson, and Thomas L. Steinmeier. 2000. “Social Security Earnings and Projected Benets.” In

Forecasting Retirement Needs and Retirement Wealth, edited by Olivia S. Mitchell, P. Brett Hammond, and Anna M.

Rappaport, 327-360. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Munnell, Alicia H., Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher, and Sara Ellen King. 2017. “Do Women Still Spend Most of Their Lives

Married?” Issue in Brief 17-14. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Munnell, Alicia H., Geoffrey Sanzenbacher, and Mauricio Soto. 2007. “Working Wives Reduce Social Security

Replacement Rates.” Issue in Brief 7-15. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Purcell, Patrick J. 2012. “Income Replacement Ratios in the Health and Retirement Study.” Social Security Bulletin

72(3): 37-58.

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 17

Raley, Kelly R., Megan M. Sweeney, and Danielle Wondra. 2015. “The Growing Racial and Ethnic Divide in U.S.

Marriage Patterns.” Future Child 25(2): 89-109.

Stevenson, Betsey and Justin Wolfers. 2007. “Marriage and Divorce: Changes and Their Driving Forces.”

Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(2): 27-52.

Wu, April Yanyuan, Nadia S. Karamcheva, Alicia H. Munnell, and Patrick Purcell. 2013. “How Do the Changing Labor

Supply Behavior and Marriage Patterns of Women Affect Social Security Replacement Rates?” Working Paper 2013-

16. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 18

Technical appendix

The analysis draws from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative longitudinal survey that has

interviewed people over age 50 every two years since 1992. It uses all 15 waves of the HRS (1992-2020) to examine

the wealth and changing demographics of women in different birth cohorts.

It also supplements the HRS with restricted

administrative earnings data provided by the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA).

Documenting women’s lifetime marital status

The calculation of the percentage of years spent married is based on detailed survey questions about current and past

marital status.

12

Women in earlier cohorts are followed until 2020, when most are well into their eighties or beyond.

However, later cohorts cannot be observed beyond their mid-to-late fties. To address potential bias from truncating

the observation period, we adjust the estimates for later cohorts based on how the oldest cohorts fared as they

aged beyond their fties. This adjusted estimate starts with the ratio of the percentage of years spent married for the

(oldest) HRS cohort as of 2020 to the percentage for this same cohort at ages 54-60:

This ratio is then applied to the reported percentages at ages 54-60 for the younger cohorts. The adjusted share of

years married is then used to categorize women into three groups: 1) never married; 2) mostly single (less than 50

percent of adult years married); and 3) mostly married (more than 50 percent of adult years married).

Calculating household wealth

The analysis includes all sources of retirement wealth: 1) Social Security wealth as measured by the expected

discounted value of future benets; 2) wealth in employer-sponsored retirement plans, including both dened

contribution and IRA balances and the present discounted value of expected benets from a dened benet plan; 3)

nancial assets less any outstanding debt;

and 4) the value of the primary residence less any outstanding mortgage

debt. The method for calculating each wealth component is described below.

Social Security. The calculation of Social Security wealth is common in the literature.

13

The starting point is the

individual’s annual Social Security benet, which is a function of Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME) and claiming

age. The AIME calculation relies on a link between the publicly available HRS and the restricted SSA earnings data.

14

The annual benet is calculated from AIME using a legislated formula, assuming that individuals claim at their Full

Retirement Age. To convert this annual income stream to a measure of wealth, future benet ows are adjusted for

legislated cost-of-living adjustments and the probability that individuals are still living, and then discounted back to age

60.

15

For married women, household Social Security wealth includes not only individual benets for both spouses, but

also the present discounted value of spousal and survivor benets, adjusted for the probability of receipt.

Employer-Sponsored Retirement Plans. For both dened benet (DB) and dened contribution (DC) retirement plans,

we follow Gustman et al. (2010) to calculate wealth based on self-reported data. DB wealth is based on estimates of

pension income at the participant’s expected retirement age. Similar to Social Security, the analysis takes this income

stream and calculates the expected present value of lifetime benets.

16

Respondents who report having a DC plan,

(1)

12 Women were eliminated from the sample in cases where the responses on marriage history are missing or inconsistent, such as a marriage starting before a previous one

ended.

13 See Fang and Kapinos (2016); Fang, Brown and Weir (2016); and Gustman, Steinmeier, and Tabatabai (2014).

14 For individuals who have yet to reach retirement age, future earnings are projected using a ve-year weighted average of their past earnings, rolled forward each year (see

Mitchell, Olson and Steinmeier 2000 for a detailed description of the methodology).

15 Assumptions about ination and real interest rates are drawn from the Social Security Trustees Report. Survival probabilities are drawn from SSA life tables by birth year

and sex.

16 As in Mitchell and Moore (1997) and Gustman, Steinmeier, and Tabatabai (2010).

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 19

such as a 401(k) or 403(b), in either their current job or a previous one are asked for the account balance. DC wealth is

simply the total balance of all accounts, plus the balance of any IRA accounts.

Housing Wealth. Housing wealth is dened as the net value of the primary residence, which is calculated as the gross

value of the primary residence less any relevant mortgages and home loans. For households where debt exceeds

equity, housing wealth is allowed to be negative.

Financial Wealth. Financial wealth includes the net value of stocks, mutual funds, bonds and bond funds; the value

of checking, savings, and money market accounts; certicates of deposit; and government savings bonds (excluding

holdings of any of these assets in DC plans or IRAs); minus non-housing debt. For households where debt exceeds

assets, nancial wealth is allowed to be negative.

Calculating replacement rates

The analysis also calculates the replacement rate for each household, which is the ratio of the retirement income that

could be generated by the household’s resources divided by its pre-retirement income. The numerator of this ratio is

estimated by converting wealth totals to annual ows assuming that households purchase an actuarially fair single-

life immediate annuity. Although few households voluntarily annuitize wealth, annuities are a proxy for a sustainable

withdrawal rate. For the denominator, the analysis takes the average of the highest ve years of household earnings

before age 55, based on the SSA administrative earnings records.

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 20

About the authors

Alicia H. Munnell is the Peter F. Drucker Professor of Management Sciences at Boston College’s Carroll School of

Management. She also serves as the director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Before joining Boston College in 1997, Alicia Munnell was a member of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers

(1995-1997) and assistant secretary of the Treasury for economic policy (1993-1995). Previously, she spent 20 years

at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston (1973-1993), where she became senior vice president and director of research

in 1984. She has published many articles, authored numerous books, and edited several volumes on tax policy, Social

Security, public and private pensions, and productivity.

Alicia Munnell was co-founder and rst president of the National Academy of Social Insurance and is currently a

member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Institute of Medicine, and the Pension Research Council at

Wharton. She is a member of the board of The Century Foundation, the National Bureau of Economic Research, and the

Pension Rights Center. In 2007, she was awarded the International INA Prize for Insurance Sciences by the Accademia

Nazionale dei Lincei in Rome. In 2009, she received the Robert M. Ball Award for Outstanding Achievements in Social

Insurance from the National Academy of Social Insurance. In 2015, she chaired the U.S. Social Security Advisory

Board’s Technical Panel on Assumptions and Methods.

Alicia Munnell earned her B.A. from Wellesley College, an M.A. from Boston University, and her Ph.D. from Harvard

University.

Siyan Liu is a research economist at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. Her research interests

are in the nancial well-being of older workers, retirement preparedness, and public pension plans. Before joining the

center, Liu earned a Ph.D. from North Carolina State University in the eld of labor economics. She holds a M.A. in

economics from Vanderbilt University and a B.B.A. from the University of Hong Kong.

Laura D. Quinby is a senior research economist at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. She conducts

research on state and locally administered retirement programs—including pensions, disability and retiree health

insurance, Medicaid, and state initiatives to expand private-sector coverage—as well as Social Security. Quinby earned

a Ph.D. in public policy from Harvard University in the elds of labor economics and public nance. Her work appears

in academic journals, such as the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management and the Journal of Pension Economics and

Finance, as well as issue briefs that are widely cited by policymakers and the media.

After 50 years of progress, how prepared are women for retirement? 21

(06/22)

TIAA Institute is a division of Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America (TIAA), New York, NY. ©2022 Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America-College

Retirement Equities Fund, 730 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

About the TIAA Institute

The TIAA Institute helps advance the ways individuals and institutions plan for

nancial security and organizational effectiveness. The Institute conducts in-

depth research, provides access to a network of thought leaders, and enables

those it serves to anticipate trends, plan future strategies, and maximize

opportunities for success.

To learn more, visit www.tiaainstitute.org.

Join the conversation online:

@TIAAInstitute